Note: This post is part of the January 2026 RPG Blog Carnival, hosted by Hipsters and Dragons. The theme this month is “Fantasy Locations,” so if you’re looking for more ways to make your world feel alive, be sure to check out this post and the other entries!

I’m not the biggest fan of the band Cream, but the song White Room is undoubtedly killer. However, the catchy chorus covers the song’s darker message: the white room is Pete Brown’s London flat, where he detoxed — it was not a joyful place.

And I’m here to tell you that white rooms are equally depressing (well, maybe that’s a stretch) for TTRPG players and GMs alike.

I often hear people complain that combat in DnD is a snooze-fest; pick your obvious best course of action, roll dice, repeat. Maybe move a little if you need to hide behind cover or get in range. Boring.

Sure, white rooms are useful for optimizers when they’re calculating damage per round. And, as a content creator who talks a lot about spell optimization, I’ll admit that I’m guilty of this myself.

But I’m happy to say that I’m not guilty of it as a DM for my party. I strive to make every combat encounter unique for my players. How? Well, lots of ways, but my #1 trick is making the location the third participant of the fight. Just because it doesn’t have a stat block, doesn’t make it any less threatening. In fact, it’s often more threatening, because you can’t kill the environment (unless you’re a high-level spell caster or an oil company).

Just think: no action scene worth its salt has its heroes fighting in a stationary place, trading attacks with the villain until one of them loses.

- Indiana Jones on the tank: The fight on the tank tracks in The Last Crusade turns a vehicle chase into a moving dungeon where the “floor” is actively trying to kill you. The threat isn’t the Nazi soldier’s punch damage, but the constant Strength saves required to avoid being dragged into the treads or crushed against the canyon wall.

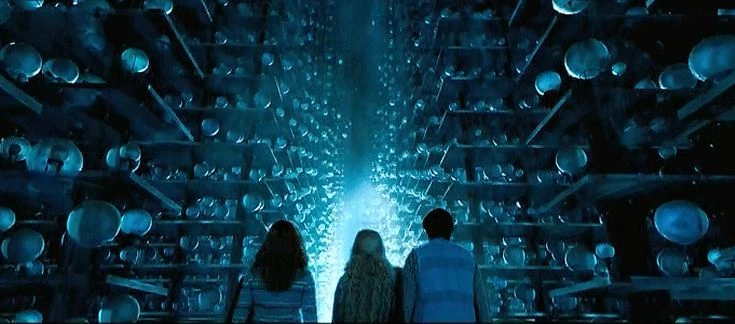

- Luke vs. Vader in the throne room: Their final duel uses the shadows and architecture to dictate the pacing of the encounter. Luke attempts to disengage and use Stealth to hide under the catwalks, but Vader counters by attacking the structure itself, proving that destructible terrain can be a more effective weapon than a lightsaber.

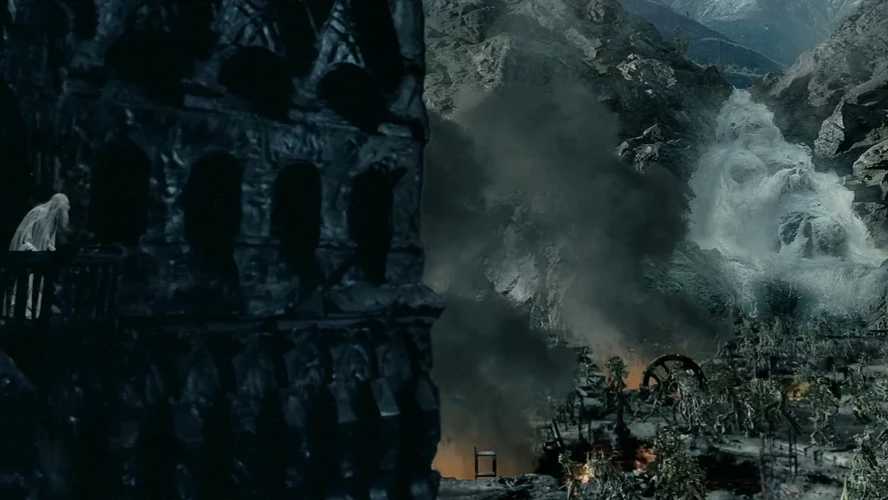

- The Mines of Moria: Why is this once great kingdom abandoned? The mysterious “Durin’s Bane” – even Gandalf doesn’t know what threat lies in wait, but he knows it was powerful enough to eradicate a whole society, making the Balrog reveal all the more epic. The Bridge of Khazad-dûm, once a defensive powerhouse for the dwarves, becomes a trap for the party, forcing Gandalf to destroy the terrain itself to defeat a foe that has too much HP to kill conventionally.

Combat locations in fantasy settings don’t just improve the tactics; they tell the story. So, let’s kill the White Room once and for all with these nine ways to make your world feel dangerous, dynamic, and alive.

We’ll Never Survive: Hazardous Locations

“Nonsense. You’re only saying that because no one ever has.”

The most straightforward way to treat the environment as a “third participant” is to give it teeth. In a standard encounter, players often view their hit points as a resource to be spent only when the enemy attacks. But when the room itself is trying to kill them, that resource economy changes drastically.

Hazards force urgency. They deny players the safety of a “camp spot” and demand constant re-evaluation of the board state. If standing still hurts, your players will move. If the environment is deadly, the enemies can use it as a weapon — and clever players can turn that weapon back on them.

Damage over Time

One of the simplest ways to make your fantasy location feel alive is to make specific zones punish players (or monsters) for lingering. Examples of locations like this I’ve used in my games include:

- The Alchemist’s Lab: Vats of experimental acid bubble over every round, expanding the “splash zone” by 5 feet every round until a valve is turned.

- The Hive: Swarms of biting insects occupy the center of the room; ending your turn there deals piercing damage, forcing players to stick to the perimeter.

- The Forge: The floor is made of metal grates over magma; if a creature is prone on the metal, they take heat damage (incentivizing shove attacks).

- The Acid Burst: Think of Heigan the Unclean, a boss in classic WoW’s Naxxramas, who shoots up acid in a cyclical, predictable way. Couple this by randomly teleporting a player out of the room, and the fight becomes a dance where you can’t afford to make a single misstep.

The Looming Threat

Sometimes, the threat of big damage is enough. This removes space from the players, while also allowing them to use it to their advantage against enemies.

- The Avalanche: A combat on a snowy slope where loud spells (Thunderwave/Shatter) trigger an avalanche that deals bludgeoning damage to creatures lower on the slope and knocks them prone/restrains them if they fail a Dexterity check.

- The Ritual: A portal widens every round, threatening to pull everyone within 30 feet into the Abyss if not closed in time.

- The Rising Tide: Acidic water rises 5 feet every round in a silo, forcing the fight vertically up a spiral staircase.

The Triggered Trap

These are hazards that lie dormant until a creature creates the wrong condition.

- The Myconid Colony: Puffball mushrooms that explode when they take even 1 damage (beware Fireballers!), dealing AoE poison damage to all creatures around them.

- The Arcane Library: Glyphs on the floor that trigger Thunderwave if a creature casts a spell while standing on them (or within X feet of them).

- The Crystal Cavern: Sharp resonating crystals that shatter and deal slashing damage if a creature moves more than half their speed nearby.

Hold Onto Your Butts: Dynamic Locations

There is a phenomenon in TTRPGs I call “turretting.” A player finds a good spot, plants their feet, and refuses to move for the entire combat because moving lowers their damage output (the mechanics of opportunity attacks don’t help, but that’s a subject for a different article). It’s efficient, but it’s incredibly boring.

Dynamic locations cure this by forcing the tactical situation to evolve every single round. When the map moves the miniatures for you, or when the geometry of the room shifts, the “perfect spot” from round 1 becomes a death trap by round 3.

Forced Movement

If the map moves the minis for you, the tactical situation changes every round.

- The Conveyor Belt: In a factory setting, belts move creatures standing on them 15 feet per round toward a rock crusher.

- The Magnetized Pillar: At the top of the round, all creatures wearing metal armor are pulled 10 feet toward a central pillar.

- The Rushing River: Characters in the water are pushed 20 feet downstream every round; if they hit a rock, they take bludgeoning damage.

Shifting Geometry

The physical layout of the room changes, altering line of sight and pathing.

- The Clocktower Gears: Giant cogs that rotate 90 degrees at the end of the round; if you’re standing on one, you get rotated away from your target.

- The Floating Islands: Chunks of earth drifting in the Astral Plane that collide and separate; jumping between them requires Athletics checks.

- The Living Dungeon: A Flesh Golem room where the walls are muscle; they contract every round, making the room narrower in some areas.

Vehicular Chaos

Fighting on top of something that is moving adds urgency and momentum.

- The Airship Deck: Strong crosswinds threaten to blow small creatures off the deck (requiring Strength saves) or impose Disadvantage on ranged attacks.

- The Chariot Race: Combat takes place across two speeding chariots; failing a Dex save means falling off and taking massive road rash damage.

- The Elevator: A fight on a descending platform where new enemies jump on from passing floors every round.

Release the River: Destructible Locations

Static maps are forgettable because they are permanent. But an unforgettable location is one that bears the scars of the battle. If a Wizard casts Fireball in a library, the map shouldn’t look the same afterward. If a Barbarian misses a swing with a Greataxe, the pillar behind the goblin should take the hit.

Destructible environments turn the scenery into a resource. Cover creates safety until it is destroyed. Bridges provide passage until they are cut. This layer of interactivity allows martial classes to feel like superheroes and spellcasters to feel like forces of nature, reminding everyone that their actions have tangible consequences on the world around them.

Fragile Footing

The ground beneath the players is a resource that can run out.

- The Glass Skylight: A fight atop a glass dome. Missed attacks with bludgeoning weapons crack the glass; a second hit shatters it, dropping everyone.

- The Ice Sheet: Fire damage targeted at the ground turns the floor from “Normal Terrain” to “Water” (Difficult Terrain).

- The Rotting Wood: An old bridge where rolling a Natural 1 on an attack or save causes the plank beneath you to snap.

Tactical Demolition

Players can use their Actions to alter the map permanently.

- The Load-Bearing Pillar: A cracked stone column that, if destroyed, collapses a section of the ceiling on top of the boss.

- The Floodgates: Lever-operated gates that, when destroyed or opened, flood the room, extinguishing fires and pushing creatures.

- The Rope Bridge: It can be cut as an action, turning a path into a swinging hazard or cutting off enemy reinforcements.

Volatile Contents

Objects in the room that react explosively to combat.

- The Flour Mill: Sacks of flour that, if burst open, create a highly flammable dust cloud that obscures vision (and creates a big explosion if ignited).

- The Alchemist’s Fire Stockpile: Crates that explode in a 10-foot radius if hit by an arrow.

- The Overloaded Crystal: A magical battery that arcs lightning at a random target every time it takes damage.

History Became Legend: Historical Locations

A “White Room” isn’t just a room without furniture; it’s a room without a past. As GMs, we often treat battle maps as isolated tactical grids, but the best locations tell a story before the initiative dice are even rolled. Story-driven geometry means ensuring every tactical advantage doubles as a lore drop.

When you design a map, ask yourself: Who built this? What was it used for? Why is it ruined? When the terrain features are rooted in the world’s history, the players aren’t just fighting a stat block; they are fighting in a living, breathing part of your setting.

The “Because” Test

Why is the map shaped this way?

- The Choke Point: This bridge is narrow because the Dwarves built it to defend against Orc hordes.

- The Open Hall: The room is massive and empty because it was a ballroom for Cloud Giants (No cover, long sightlines).

- The Maze: The corridors are twisting because the paranoid wizard wanted to confuse intruders (lots of corners for ambushes).

Architectural Storytelling

Using terrain features to convey the culture of the location.

- The Statues: The “cover” isn’t generic rocks; it’s the petrified remains of previous adventurers.

- The Frescoes: Murals on the walls that actually reveal the weakness of the Golem guarding the room if a player successfully investigates them.

- The Ruined Throne: The “high ground” is a toppled throne, symbolizing the fall of the kingdom.

Lingering Magic

The history of the location manifests as magical effects.

- The Wild Magic Zone: A crater where a wizard tower exploded; casting a spell of 1st level or higher triggers a Wild Magic Surge.

- The Hallowed Ground: An ancient temple floor that grants temporary HP to anyone who ends their turn praying.

- The Cursed Soil: A battlefield where necromancy was used; any creature that dies here immediately rises as a zombie.

Nature Has Spoken: Weather-Driven Locations

Sometimes the enemy isn’t the Goblin; it’s the hurricane the Goblin is standing in. We often treat weather as “flavor text” to read at the start of the session, but weather is the great equalizer. It falls on the just and the unjust alike, ruining the plans of heroes and villains with equal indifference.

Weather adds a layer of texture to the combat. It disrupts line of sight, makes movement difficult, and imposes a physical tax on anyone foolish enough to fight in it. By mechanizing the weather, you turn a standard encounter into a survival challenge.

The Visibility Tax

Weather that messes with line-of-sight and targeting.

- Heavy Rain/Fog: Imposes Disadvantage on ranged attacks beyond 30 feet.

- Snow Blindness: Bright sun reflecting off snow requires a Con save or results in the Blinded condition for 1 round.

- Sandstorm: Blocks vision entirely beyond 10 feet, turning a long-range encounter into a melee brawl.

The Physical Toll

Weather that saps resources or HP.

- Extreme Heat: Characters in heavy metal armor take fire damage or risk Exhaustion if they don’t find shade/cool water.

- Extreme Cold: Characters without cold-weather gear must make Con saves every hour or gain Exhaustion.

- Hurricane Winds: Flying is impossible; flying creatures must land or be thrown 60 feet in a random direction.

Changing the State

Weather that alters the terrain itself during the fight.

- The Mud Pit: Heavy rain turns 2d6 squares of normal dirt into difficult terrain after each round.

- The Flash Freeze: A sudden drop in temperature freezes the river, allowing players to walk on water (but slip on ice).

- The Lightning Strike: During a storm, anyone standing on the highest point of the map (or wearing metal) is a lightning rod on Initiative 20.

Then We Will Fight in the Shade: Locations with Cover

In a “White Room,” a bandit with a shortbow is a math problem. In a well-designed location, that same bandit is a tactical puzzle. Hard defense breaks the monotony of “I attack, I hit, I end turn.”

Cover forces movement. It demands that players flank, reposition, and utilize the “Ready Action” to catch enemies popping out to shoot. By providing varied types of cover, you stop players from staring at their character sheets and start making them consider the map, looking for the one angle that gives them the shot.

Hard Cover with Perks

Don’t just give them a wall. Give them cover with special properties.

- The Arrow Slits: Grants +5 AC (Three-Quarters Cover) but limits the PC’s vision to a narrow cone.

- The Magic Shield: A translucent barrier that blocks spells but allows physical arrows to pass through.

- The One-Way Mirror: A magical pane where creatures have total cover and can see out, but enemies cannot see in.

Soft Cover & Obscurement

Things that make you hard to see, but won’t stop a bullet.

- The Steam Vent: Clouds of steam that provide heavy obscurement (can’t be targeted by spells that require sight) but offer no AC bonus.

- The Hanging Tapestries: You can hide behind them, but arrows will punch right through.

- The Tall Grass: Small creatures can hide as a bonus action, but Medium creatures are fully visible.

Interactive/Risky Cover

Cover that has a cost or a consequence.

- The Banquet Table: Can be flipped as an Action to create cover where there was none.

- The Caged Monster: You can hide behind the cage, but the monster inside tries to grapple you through the bars.

- The Civilian Crowd: You can hide in the crowd of panicked commoners, but AoE attacks directed at you will kill innocents.

You Think Darkness Is Your Ally? Dark Locations

Darkness shouldn’t just be a toggle switch that gives Disadvantage on attacks. It should be a mood. In a game that relies heavily on “what you see is what you get,” removing vision is the quickest way to spike the tension at the table.

A truly dark location turns the map into a mystery. It denies information, hides numbers, and allows the GM to play with the terrifying concept of the “Unseen.”

Dynamic Illumination

Instead of “Lights Out,” try “Moving Lights.”

- The Swinging Chandelier: Casts a moving cone of bright light. Players have to time their movement to stay in the shadows (or stay in the light).

- The Strobe Effect: Lightning flashes reveal enemy positions only for a split second, forcing players to memorize the battlefield.

- The Fading Torch: The only light source is a dying torch that reduces its radius by 5ft every round.

The Unseen Threat

Using darkness to mess with player psychology.

- The Shadow Monsters: Enemies that have Advantage while in dim light and regenerate HP if they end their turn in total darkness.

- The Auditory Hallucination: In magical darkness, players hear footsteps behind them (Wisdom save or turn and attack empty air).

- The Glowing Eyes: Thousands of eyes watch from the dark ceiling; they don’t attack, but they cause Paralyzing fear if looked at directly.

Light as a Weapon

Making light a mechanic that hurts or helps.

- The Sunbeam: A single shaft of sunlight enters the crypt; Undead take damage if shoved into it.

- The Mirror Puzzle: Players must use Actions to angle mirrors to reflect light onto the invulnerable boss to make him vulnerable.

- The Bioluminescence: The cave is dark, but the moss on the walls glows neon blue when magic is cast near it, revealing otherwise invisible creatures.

I Have the High Ground: Locations with Elevation

Most battle maps are flat. This conditions players (and GMs) to think in two dimensions, treating combat like a game of checkers. But as soon as you introduce verticality, the game becomes three-dimensional chess.

Movement speed becomes a complex resource when gravity is involved. High ground offers advantages, but it also carries the risk of a lethal fall. Verticality turns the “Shove” action from a niche mechanic into the deadliest weapon on the board, and forces players to look up, down, and all around.

The Sniper’s Nest

Reward players (or punish them) for spending movement to get above the fray.

- The Elven Tree-Walk: Platforms 40 feet in the air connected by rope bridges. Archers here ignore half-cover provided by ground-level obstacles.

- The Ziggurat Steps: Moving up the stairs costs double movement (Difficult Terrain), but moving down is normal, making it easy to kite enemies.

- The Mezzanine: A balcony overlooking the ballroom. Spellcasters here can target anyone below, but melee fighters on the ground can’t reach them without dashing to the stairs.

The Long Way Down

Locations where “The Shove” action is more effective than a Greatsword.

- The Bottomless Pit: A narrow stone bridge over a chasm. A successful Shove check doesn’t just move the enemy 5 feet; it removes them from the encounter instantly.

- The Reverse Gravity Tower: The “Floor” is the ceiling. Falling means falling up 100 feet. Players must grapple onto furniture to avoid “falling” into the sky.

- The Crumbling Cliffside: The edge of the map is unstable. If a character stands within 5 feet of the edge, the ground might give way (Dex save), turning a cliff into a slide.

Climb or Fly

Terrain that requires skill checks just to navigate vertically.

- The Giant Spider’s Web: The battle takes place vertically inside a funnel web. Moving up requires an Athletics check; failing means getting stuck (Restrained).

- The Ship’s Rigging: Fighting on the masts and ropes of a pirate ship. You can swing (Acrobatics) to move 30 feet in a single Action, but falling means hitting the deck hard.

- The Waterfall: To reach the boss at the top, players must swim up the cascading water (Athletics with Disadvantage), fighting the current every round.

I’m Walkin’ Here! Urban Environments

City fights are often treated like “Dungeon corridors with a skybox.” But a real city is chaotic, crowded, and layered. In a dungeon, you are isolated; in a city, you are surrounded. The “third participant” here isn’t nature or architecture; it’s society.

Urban environments are cluttered with the detritus of civilization — carts, crowds, clotheslines, and laws. Fighting in a city means navigating a space that wasn’t designed for combat. It forces players to worry about collateral damage, witnesses, and the city watch, adding a layer of social consequence to every Fireball they cast.

The Vertical City

Cities aren’t flat. They are layers of roofs, balconies, and sewers that offer varying elevations within a single turn.

- The Rooftop Chase: Flat roofs are easy, but slanted tiles require Acrobatics to avoid sliding off. Gaps between buildings require a running start (Strength) to clear.

- The Clotheslines: Laundry strung between building blocks line of sight for archers, but allows nimble characters to zipline across the street more quickly.

- The Sewer Grate: A Small creature can squeeze through a grate to escape or flank; a Medium creature might step on a loose grate and fall into the muck below.

Collateral Damage

In a dungeon, you can Fireball freely. In a city, there are consequences, bystanders, and laws.

- The Panic Stampede: The street is full of commoners. They count as Difficult Terrain. If a loud spell is cast, they panic, forcing Strength saves to avoid being knocked prone.

- The City Watch Timer: The environment has a deadline. “You hear whistles blowing.” Every round, the threat of 2d6 Guards arriving increases, forcing a “hit and run” strategy.

- The Property Tax: Using big AoE spells destroys shop fronts. Players might win the fight but end up with a fine or a bounty for destroying the local potion shop.

Street-Level Hazards

The road itself is a busy, cluttered mess of “civilized” obstacles.

- The Runaway Cart: A carriage moves down the center of the map at Initiative 20. It acts as a moving wall (Total Cover) that crushes anyone in its path (Dex save).

- The Market Stall: Provides Soft Cover but is destroyed instantly if hit. Destroying a fruit stand turns the area into a Grease spell (Difficult Terrain/Prone).

- The Construction Pit: An open magical conduit or sewer repair site. It’s a 10-foot deep pit in the middle of the road, perhaps obscured by a flimsy wooden plank.

Bringing It To The Table: Implementation Tips

Designing a location with lava, gears, and chandeliers is the easy part. The hard part is getting your players – who may be conditioned to stand still and attack – to actually use them. Here is how you break the “White Room” habit at the table.

Chekhov’s Set Dressing

There is a rule in theater: if you show a gun in the first act, it must go off in the third. In DnD, if you describe a heavy oak bookcase, someone better be able to tip it over.

- Don’t just describe visuals; describe affordances. Instead of “There is a chandelier,” say “There is a chandelier with a very rusty chain.”

- Spell things out. Sure, players are clever. But they often don’t know what’s possible unless you tell them.

-

The “Yes, And” Rule: If you describe the ground as loose gravel and a player asks if there is a loose stone to throw at a button, the answer is yes. If you describe a massive tapestry and they ask if they can tear it down to temporarily “blind” enemies below it, of course. If you describe it, players can use it.

Even if you don’t describe something initially, if a player asks, “Does the room have any X in it?” and it makes sense that there would be, say yes, and see what they do with it!

The “UI” of the Mind

In a video game, glowing red cracks on the floor tell you, “Don’t Stand Here.” In a TTRPG, players often play it safe because they don’t know the rules of your room. You need to be their User Interface.

- Telegraph the mechanics. Don’t make them guess. Tell them: “The conveyor belt looks like it moves about 15 feet per round.” Or “The mushrooms give off a noxious smell, and look fragile enough to burst at the slightest touch.”

- Reveal the DCs. This is controversial to some, but I find that it speeds up combat and decision-making. “If you want to jump across the chasm, that’s a DC 15 Athletics check. If you fail, you’ll fall 30 feet.” Knowing the odds encourages risky, cinematic plays.

- Highlight the “Toys.” At the start of combat, explicitly list the interactive elements. “You see goblins, but you also see a vat of acid, a weak bridge, and a pile of explosive barrels.”

Monkey See, Monkey Do

If players ignore your cool terrain, have the monsters use it against them. The best way to teach a player that the arcane crystals react to magic effects is to have the enemy spell caster use them to their advantage.

- The Tutorial Round: Have the first enemy take a “Terrain Action.” Have a Kobold cut a rope to drop a sandbag. Have an Orc shove a player into the fire.

- Immunity is a Clue: If the enemies are wearing heavy goggles, that tells the players a “Sandstorm” or “Blinding Light” event is coming.

- King of the Hill: If the boss refuses to leave the raised dais (where she gets a bonus to hit creatures below her), the players will naturally realize that the dais provides a tactical advantage and try to take it.

See It In Action: The Creative Game Master’s Guide

If you’re looking for a resource that embodies this “Anti-White Room” philosophy, I highly recommend checking out a book on the same theme as this month’s carnival: The Creative Game Master’s Guide to Extraordinary Locations by Duncan Rhodes. I’ve been reading through it, and what stands out is that the locations aren’t just “pretty backdrops” — they are built with mechanics that force interaction.

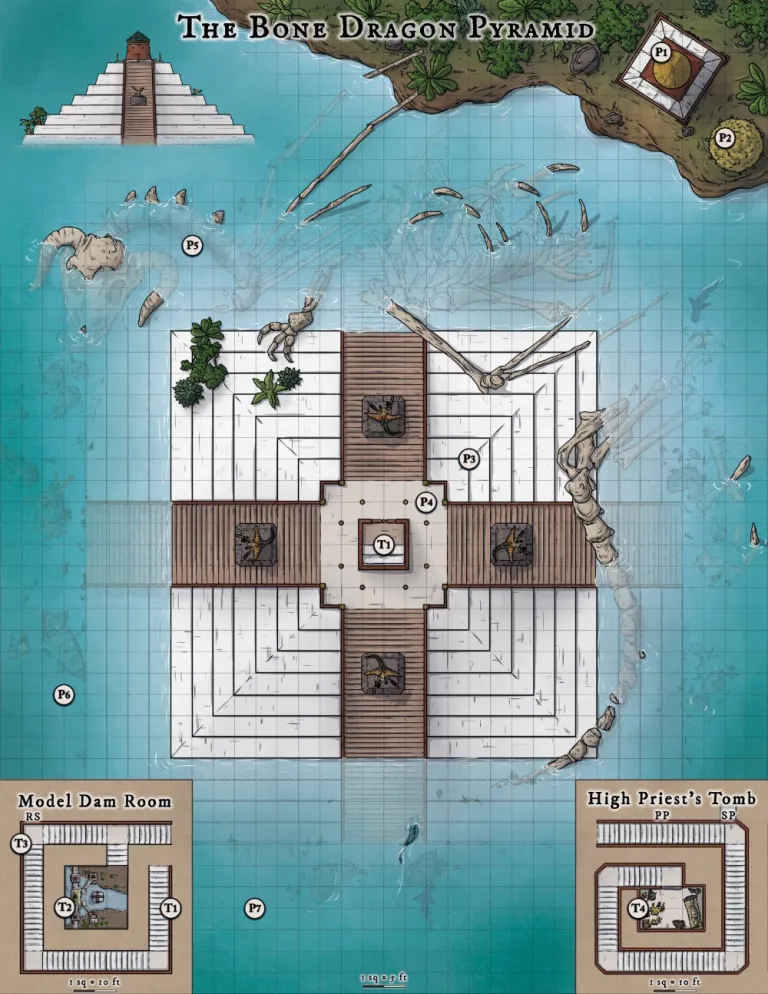

Take the Bone Dragon Pyramid (the map featured above). It hits almost every single category of “Alive” design I mentioned in this article:

- Hazardous Locations: The water surrounding the temple isn’t just “difficult terrain”; it is a Hazard Zone. The text specifies that the lake is “rife with river sharks” that “respond quickly to creatures flailing around,” so when the Jagultodile guardians knock you into the water, your problems get a whole lot worse.

- Elevation & Movement: The map uses verticality as a resource cost. The Holy Staircases penalize movement speed for going up, while the Terraced Steps require Athletics checks to climb. This mechanically reinforces the “High Ground” advantage for the defenders at the top.

- Dynamic Elements: The interior features a Rolling Sphere Trap. This isn’t a “save or suck” moment; it initiates a chase scene. Players have to roll initiative against the trap and make active choices — racing to safety, diving into alcoves, or getting crushed. It turns the corridor into a moving conveyor belt of death.

- Story-Driven Geometry: The location passes the “Because” test. Why is the pyramid sunk into the water? Because “the weight of the Bone Dragon Pyramid saw it sink into the ground” over centuries. Why is there a model of a dam inside? Because it holds the “Sun Key” required to unlock a completely different adventure location. The furniture explains the world.

This is exactly the kind of design that stops a fight from being a math problem and turns it into a story. If you want more examples like this, you can pick up the book here.

The Map Is The Story

I started this article talking about White Rooms — those safe, balanced, perfectly predictable vacuums where math happens. And sure, they are fair. But TTRPGs aren’t about fairness; they are about adventure.

Your players likely won’t remember the time they fought three generic bandits in a 30×30 stone room. But they will remember the time they fought three bandits on a burning rope bridge while a waterfall crashed down on them.

Use these environmental tools to disrupt the “optimal” strategies that make combat stale. If your players love to kite every enemy, throw them into a hazardous storm where moving too far away carries a heavy cost. If they prefer to park in melee range and trade blows, use shifting floors or sporadic hazards to force them apart (without the punishment of opportunity attacks).

By taking away the safety of the obvious best tactic, you make the decision-making process harder, and the victory much more satisfying.

Now, get out there and dirty up that clean map.